What you need to know about button battery poisoning

March 16-22 is National Poison Prevention Week, and we want to talk about how to prevent button battery poisoning.

Button batteries (also called disc or coin batteries) are used to power watches, cameras, hearing aids, computer games, alarm clocks, bathroom scales, key chains and more. Because they are small, round and smooth, kids can mistake button batteries for food or candy – and swallowing one can lead to serious injury and even death.

Children under the age of six are at the highest risk of ingesting a button battery. From 2021 to 2023, the BC Drug and Poison Information Centre managed 159 cases of button battery exposures, with more than half of them (55%) involving babies and children ages five and under.

If you suspect someone has ingested (swallowed) or inserted a button battery into the ear or nose, this should be treated as quickly as possible. DO NOT induce vomiting.

Symptoms can vary and can include (sometimes there are no symptoms at all):

- Gagging or choking

- Coughing or noisy breathing

- Pain or irritability

- Drooling

- Unexplained vomiting or food refusal

- Abdominal pain

- Nose bleeds

- Unusual odour, discharge, or bleeding from the ears, nose or eyes

Immediate medical attention should be given—call 9-1-1, the BC Drug and Poison Centre at 604 682-5050, or 1 800 567-8911 or go to the nearest emergency department.

While on the way to the emergency department or waiting for help to arrive, give honey if the child is over the age of one to reduce the risk of injury if they can swallow and the ingestion happened less than 12 hours ago. Honey coats the battery and can help reduce the amount of chemical burn.

- For infants under 12 months of age, or if honey is not available, or the child has an allergy, you can use jam.

- Give 10 ml (2 teaspoons) of honey. Repeat this dose every 10 minutes for up to six doses.

- Stop at any point the person is unable to swallow.

Prevention Tips

- Reduce the number of products in your home that use button batteries.

- Safely store batteries, live or dead—in a high up or secure place and never leave them loose or lying around.

- Make sure that products that do have button batteries have screws securing the battery panel.

- When discarding used button batteries, put tape all the way around them and store in a container with a screw-top lid.

Learn More

Help spread the word: Share this page with your family and friends who interact with children under 6. Use our social media toolkit to share safety messaging around button batteries with your networks.

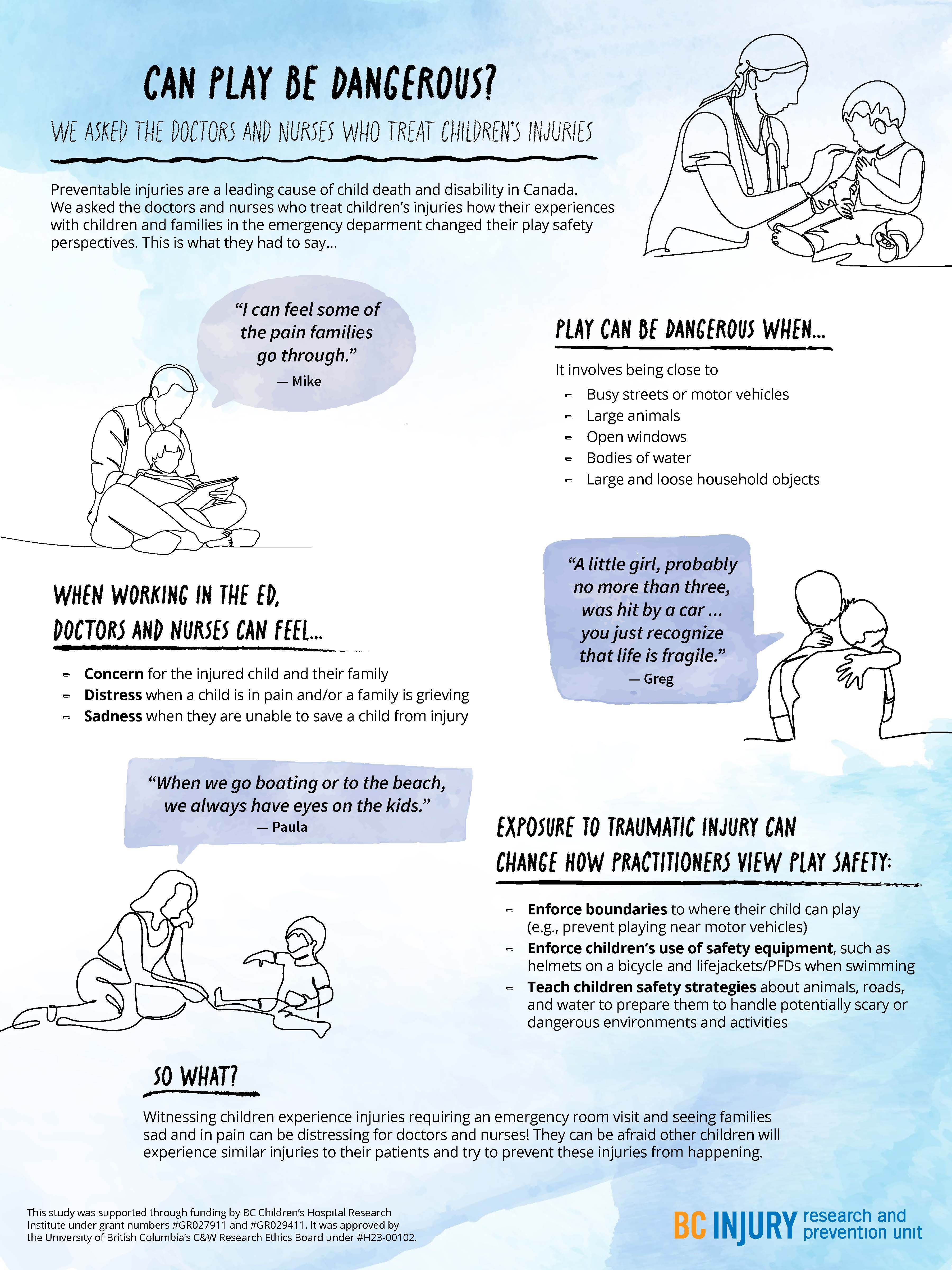

- distress when a child was in pain and when a family was grieving; and

- sadness in the event they were not able to save a child in their care.

- concern for the injured child and the child’s family;

Particularly traumatic events, such as those involving vivid sights and sounds (e.g., families holding each other and having extreme reactions), stuck with the practitioners, having long-lasting impressions on them and causing them to re-live these events in the years following their exposure.

Even after their shift was over, practitioners said that they changed how they approached parenting and how they perceived safety during play as a result of witnessing these traumatic events. They reported having more knowledge of the causes and consequences of severe injuries, such as those that require hospitalization or emergency care. For example, practitioners were more likely to enforce boundaries around where their children could play, such as by forbidding their child to play near busy streets. They also were more likely to tell their child about safe play environments and equipment, and put this equipment on their child before play, such as explaining the benefits of using helmets while riding bikes.

Practitioners were more likely to enforce boundaries around where their children could play, and use safety equipment, such as bike helmets.

Practitioners also described being concerned about their children’s play near open windows, around large bodies of water unsupervised, and in environments where firearms were present. They also expressed worry about their children’s play on trampolines and on motorized vehicles, such as ATVs. Findings related to trampoline play safety concerns were published in the journal Injury Prevention.

Observing family grief due to child injury or death affected the mental well-being of health care practitioners, drawing attention to the need for mental health supports for those involved in caring for severely injured and dying patients.

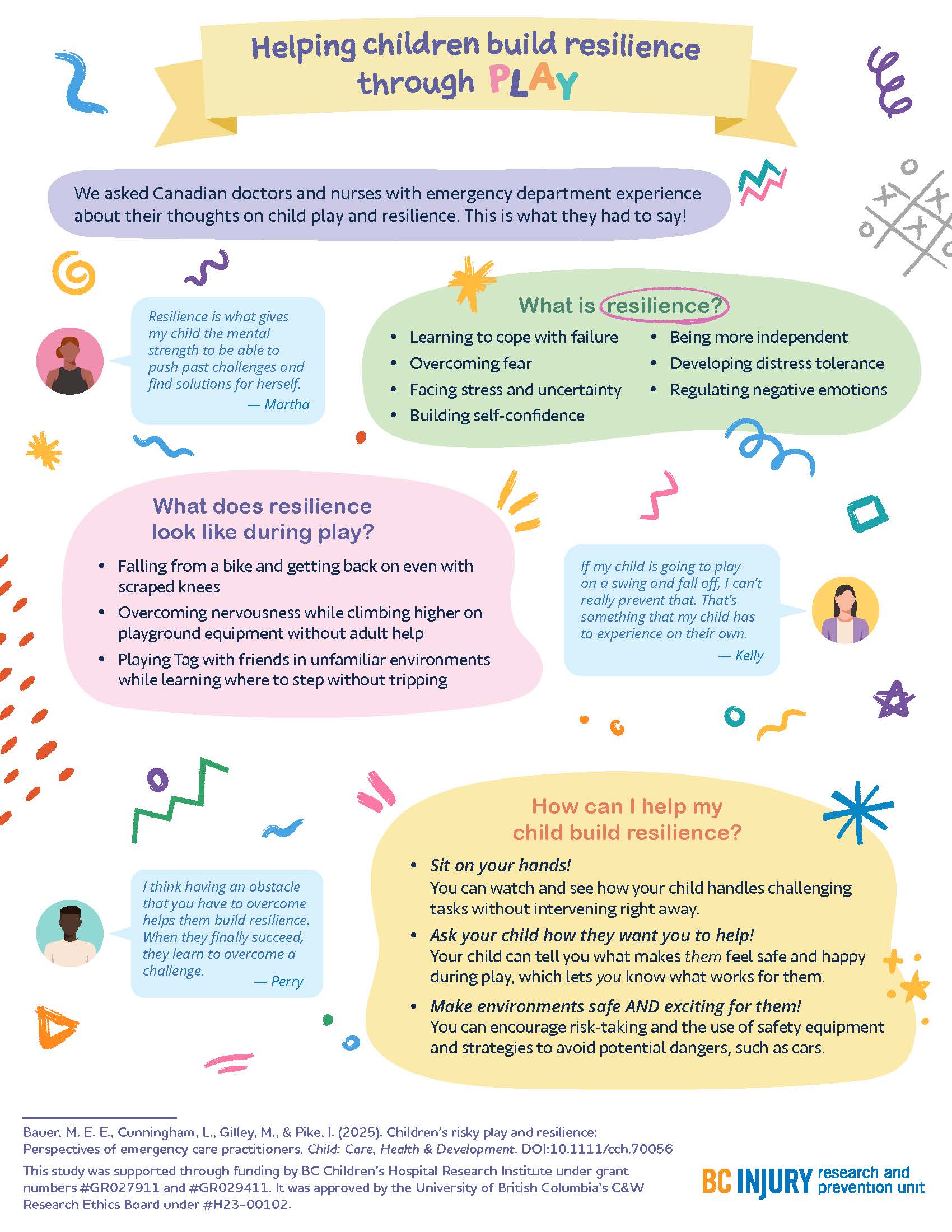

"Raise more resilient children through play...watch and see how your child handles challenging tasks without intervening right away." —Dr. Michelle Bauer

Building resilience through play

How can parents help their children build resilience? By letting them play!

The experiences that practitioners witnessed encouraged them to support their children in building resilience through play; specifically, by supporting children in learning to cope with failure, overcome fear, build self-confidence, develop distress tolerance, and regulate negative emotions. Findings related to building resilience through play were published in the journal Child: Care, Health, and Development.

Parents fostered resilience in their kids by:

- helping their kids get back on bikes after they fell off and wanted to try again;

- sitting on their hands so they did not instinctively reach for their children when their children fell down; and

- encouraging participation in challenging and thrilling activities in forests and water while safety equipment was used.

"There are a few ways that parents can raise more resilient children through play that are supported by literature and our study findings," said Dr. Bauer. "One: watch and see how your child handles challenging tasks without intervening right away."

"Two: Ask your child how they want you to help—let them tell you what makes them feel safe and happy during play. Let them lead. And three: make play both safe and exciting by encouraging risk-taking, teaching them how to avoid hazards, and using safety equipment.”

This research was supported through Drs. Bauer’s and Gilley’s receipt of a clinical and translational research seed grant from the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute (BCCHR), Dr. Bauer’s BCCHR postdoctoral fellowship award, and additional training provided to Dr. Bauer through her participation in the Programs and Institutions Looking to Launch Academic Researchers (PILLAR) program through ENRICH, a national organization training perinatal and child health researchers.

Learn more about the study through two infographic posters:

Graphics and posters by Milica Radosavljevic